One of my central Virginia besties is like me and loves old books. Before I left Farmville, we used to plan day trips throughout Virginia just for book sales. If there happened to be a Tiffany’s, Crate and Barrel, a tasty Thai restaurant, or a fun museum in the vicinity, well, we’d make it an all day fun event.

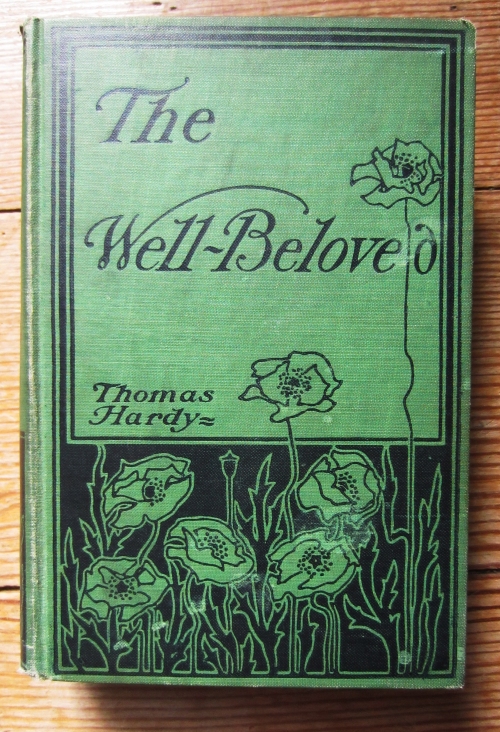

She bought this copy of Thomas Hardy’s The Well-Beloved during one of our all day adventures-our very first one together in Roanoke, in fact.

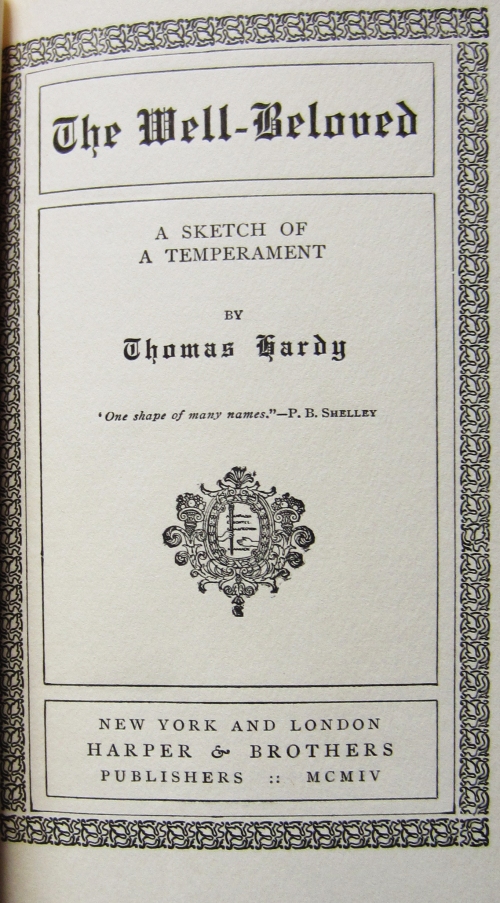

It’s Hardy’s last novel, although, one could technically argue Jude the Obscure was last, since The Well-Beloved was originally published in serial form under the title of The Pursuit of the Well Beloved throughout 1892. It was modified and published in one volume in 1897 after Jude the Obscure in 1895.

I personally have not read The Well-Beloved, and of the few novels of Hardy’s I have read, I haven’t really enjoyed them mainly because of his use of dialect. I purchased Under the Greenwood Tree when I lived in Dorset, since Hardy was born and lived most of his life there, and he used Dorset to provide a fictional setting to a majority of his novels. Hardy was known for using words or phrases that were specific to small Dorset villages, diction which has almost completely vanished. When you’re having to look up words in all of the dialogue, it gets a little old. From a historical point of view, this is great, because it captures a way of life. Despite my reservations concerning Hardy’s novels, he certainly perfected his art, writing compelling literature, works worthy of being called classics.

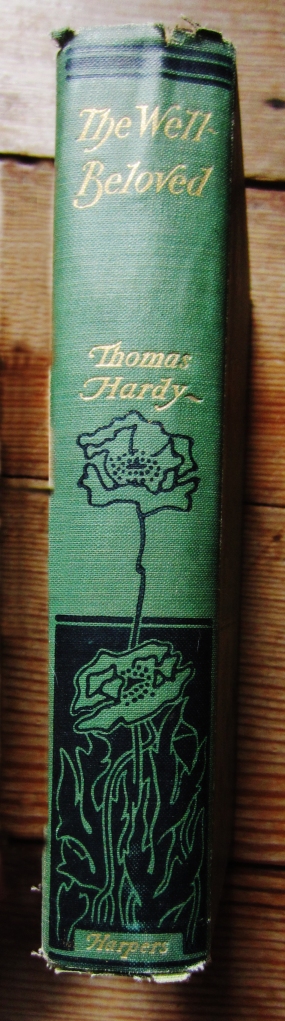

This copy was published in 1904, and is the third printing by Harper & Brothers. Its Art Nouveau spine and cover invite the reader in, with its lovely poppies and tall grasses. Based on the cover (I’m a total cover judger), I would read this book; it looks so pleasant!

Thomas Hardy was born in Brockhampton, Dorset, in 1840 to a stonemason father and a well-read mother. He was educated at home until the age of 8, then sent to a local school until the age of 16. Because his family couldn’t afford to send him to university, his parents apprenticed him to an architect. At the age of 22, he moved to London, enrolled in King’s College, and began working for Arthur Blomfield-a prominent London architect.

At the request of Blomfield, Hardy was given the task of exhuming graves at St. Pancras’ Church, one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in Northern Europe. To make way for a new underground tunnel and the structural support for an overland railway, Hardy supervised the exhumation of around 8000 graves. He relocated the headstones under an ash tree, which is still thriving almost 150 years later.

Hardy ended up not staying in London, so he returned to Dorset, began writing novels-unsuccessfully in the beginning, and continued his architecture. He married Emma Griffin in 1874, who encouraged him to keep writing. After the success of his 4th novel, Far from the Madding Crowd, Hardy quit architecture to write full time. Unfortunately for Hardy, his marriage to Griffin didn’t really work out; they quickly fell out of love and eventually became estranged. Yet, when she died in 1912, Hardy was overcome with grief and requested to be buried beside her when he died. He moved on, despite his sorrow, to his secretary, Florence Dugdale, who was thirty-eight years his junior. They married in 1914, when he was 73 and she 35.

Hardy died in January of 1928, and despite his wish to be buried with Emma, his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey in Poet’s Corner. His heart, however, is supposedly buried with Emma in Dorset. There’s rumor that when Hardy’s heart was removed, the surgeon’s cat ate it, so they substituted the original with a different heart. Interesting twist, huh.

If you really enjoy Hardy’s work and will be in England for any period of time (or, if you live there!), you should check out his birthplace in Brockhampton, Dorchester. In 2012, the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Dorset County Council teamed up to build a state of the art visitors center, as well as to open more of this idyllic thatch cottage to the public. It’s a quaint little place-definitely worth a visit.

You can also visit Hardy’s home from 1885 until his death in 1928, Max Gate, which Hardy designed himself. Located just outside of Dorchester, this is where he wrote Tess, most of his poetry, Jude, and The Well-Beloved.

If you’re in London, you should definitely go check out Hardy’s Tree at St. Pancras Old Church-off the beaten path but so cool to see!

Further Reading:

Bates, Claire. ‘Thomas Hardy’s beloved home to throw open its doors the madding crowd.’ 29 December 2010. Web. 21 October 2013 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1342170/Thomas-Hardys-home-Max-Gate-opened-madding-crowd.html

Beattie, Rebecca. ‘Nature Mystics: Thomas Hardy.’ Moon Books Blog. 10 October 2013. Weblog. 16 October 2013

Bryant, Clifton D. and Dennis L. Peck, ed. Encyclopedia of Death and the Human Experience. London: Sage Publications, 2009. Print.

Evans, R.J. ‘The Hardy Tree: An Early Work of a Great Novelist.’ Kuriositas. 24 July 2012. Weblog. 22 October 2013 http://www.kuriositas.com/2012/07/hardytree.html

Farell, John P. ‘Thomas Hardy.’ Studies of Victorian Literature: University of Texas. 25 March 2004. Web. 20 October 2013 http://www.laits.utexas.edu/farrell/documents/Hardy.pdf

Hardy, Florence Emily. The Life of Thomas Hardy 1840-1928. London: Wordsworth Literary Editions, 2007.

Hopp, E.O. ‘Thomas Hardy, Florence, and Wessex at Max Gate.’ 1914. Image. 21 October 2013 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1342170/Thomas-Hardys-home-Max-Gate-opened-madding-crowd.html

inDorset. ‘Project will open up Hardy’s well-beloved home.’ inDorset. 6 December 2012. Web. 16 October 2013 http://indorset.com/2012/12/project-will-open-up-hardys-well-beloved-home/

King’s Cross Central Limited Partnership. ‘St. Pacras Old Church.’ King’s Cross. 2013 Web. 22 October 2013 http://www.kingscross.co.uk/st-pancras-old-church

National Trust. ‘Max Gate.’ National Trust. 2013. Web. October 20 2013 http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/max-gate/

National Trust. ‘Hardy’s Birthplace.’ National Trust. 2013. Web. October 20 2013 http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hardys-birthplace/

Price, Claire. ‘Dorset Dialect.’ BBC News. 4 April 2008. Web. 21 October 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/dorset/content/articles/2007/05/18/dialect_feature.shtml

Shaw, Phillip. ‘Why it matters: Saving St. Pancras Old Church.’ Kentishtowner. 13 May 2013. Web. 22 October 2013 http://www.kentishtowner.co.uk/2013/05/13/why-it-matters-saving-st-pancras-old-church/