Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

The Gunpowder treason and plot;

I know of no reason

Why the Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

So starts the poem which marks November 5th as Bonfire Night in Great Britain. It is made famous in the States most notably by the movie and comics of V for Vendetta. This little poem continues on, telling the tale of conspiracy and rebellion, as well as including a little ditty about the Pope.

On the eve of November 4th, 1605, a spy for King James I caught Guy Fawkes, a rebellious young man of 23, red-handed as he was setting up 36 barrels of gunpowder directly beneath the Parliament’s House of Lords. The next morning, the King was to reopen the first session of Parliament, in which the King, his heir, and all the Lords of the realm would be present.

To really understand why Fawkes felt it necessary to destroy the King and all of Parliament, we’ll have to go back a little further than 1605, back to the end of Bloody Mary‘s reign in 1558. As many may know, Mary restored Roman Catholicism after her half-brother (Edward VI) and cousin’s (Lady Jane Grey) short Protestant reigns. She enforced religious persecution throughout England for Protestant dissenters, and had around 300 individuals burnt at the stake. All within a five year period. When Mary’s half-sister, Elizabeth I, took the throne after Mary’s death, Elizabeth reinstated Protestantism, getting herself excommunicated from the Catholic church in the process. With Elizabeth’s death in 1603, James I continued this reign of Protestantism, to the disappointment of many Catholic sympathizers.

Guy Fawkes was one of these sympathizers. Born in 1570 in York, England, Fawkes’ parents raised him as a Protestant; however, his maternal grandparents were ‘recusant’ Catholics,refusing to attend Protestant services. At the age of eight, his father died and his mother married a Catholic, further influencing his decisions against Protestantism. By 1601, Guy left for Europe, joined the military for Catholic Spain fighting against Protestant Dutch in the Eighty Years War. During this time period, Guy petitioned the Spanish king for help to overthrow the ‘heretic’ King James I without luck.

James I by John De Critz the Elder before 1647. In the Collection of London’s National Portrait Gallery.

It was during this time in Spain when Fawkes was asked to join a conspiracy known as the Gunpowder Plot against James, with Robert Catesby at the plan’s helm. Guy was given the most important job of lighting the 36 cases of gunpowder, narrowly escaping across the Thames. His co-conspirators had planned to start an uprising in the East Midlands, kidnap James’ daughter, and use her as a puppet queen until they could marry her off to a Catholic, ultimately restoring the Catholic monarchy. After a tip off to one of the members of Parliament (or so the story goes), the area was searched, catching Fawkes hours before lighting his stockpile of gunpowder barrels.

Fawkes was arrested and tortured, eventually naming his co-conspirators. Some were arrested while others were killed while resisting arrest. In January of 1606, Fawkes was tried and sentenced to a traitor’s death: to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

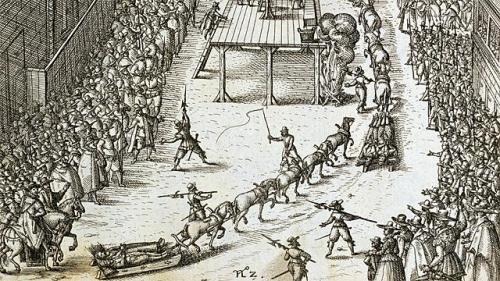

German engraving depicting the execution of Guy Fawkes, 1606. Photo courtesy of Bridgeman Art Library Ltd and the BBC.

At his execution, rumor is that Fawkes jumped from the Gallows, breaking his neck, thereby avoiding being cut down and ripped apart all while still alive. Since he dodged the worst of his execution, the King ordered his body to be hacked to pieces, sending them to the four corners of the kingdom as a warning to others.

One of the things that boggles my mind is that Fawkes was a late addition to the conspiracy, a follower, and the only one caught before he was racked, identifying the others in the group. He is the only one that is personified in Bonfire Night celebrations, and across the country, effigies of Guy Fawkes burn each year.

Further Reading:

Altman, Alex. ‘A Brief History of Guy Fawkes Day.’ Time World. 5 November 2008. Web. 4 November 2013 http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1856603,00.html

Habing, B. ‘The Fifth of November: English Folk Verse.’ Poem of the Week. 17 December 2006. Web. 4 November 2013 http://www.potw.org/archive/potw405.html

BBC. ‘Guy Fawkes.’ BBC HISTORY. 2013. Web. 4 November 2013 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/people/guy_fawkes

Greenspan, Jesse. ‘Guy Fawkes Day: A Brief History.’ History. 5 November 2012. Web. 4 November 2013 http://www.history.com/news/guy-fawkes-day-a-brief-history

Trueman, Chris. ‘Guy Fawkes.’ History Learning Site. 16 February 2011. Web. 4 November 2013 http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/Guy-Fawkes.htm

My mother was from London and described the celebration for Guy Fawkes Day when she was a little girl in the 1930s. They would get some old clothes and then stuff it with paper or straw. Then They would the put the stuffed person in a wagon and go door to door saying “penny for the Guy” (like going door to door for Halloween). That evening when they had the fire works (like our 4th of July) they would also have a bonfire at which time everyone would through their “Guy” on the fire. In the end they would all buy baked pototes and watch the fire works.

Those are such great memories! I somehow missed all the celebrations when I was in England. I don’t remember any of my friends saying anything about going door to door like we do for Halloween. I wonder if this is still a tradition?